Browser in the Browser Attacks

A quick view on what Browser-In-The-Browser (BITB) attacks are and how to spot one.

What is a Browser-In-The-Browser (BITB) attack?

A browser in a browser attack put simply is a phishing technique that allows an attacker to spawn a pop-up window in the user’s browser that appears to link to a legitimate website. It’s primarily used to mimic legitimate third-party authentication methods in an attempt to steal login credentials.

Phishing is a type of social engineering where an attacker would typically send the target some form of email claiming to be someone else, or promoting some sort of website with a malicious link.

Where is this exploited?

Many online services nowadays allow you to log in with another service. As an example, a website like Canva allows you to log in or ‘continue’ with a range of services such as Google, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft and Clever, as well as the typical email login.

When any of these are clicked, a small pop-up window appears with the login page for whatever service you decided to use.

These authentication pop-up windows are what attackers use for a BITB attack.

How do they do this?

For an attacker to make a convincing phishing page, they need at least one of the following, but typically both:

The webpage must look the same.

The URL must look the same, or be so similar that someone would miss the mistake.

URL Example: twiter.com vs twitter.com or facebook.com vs focebook.com

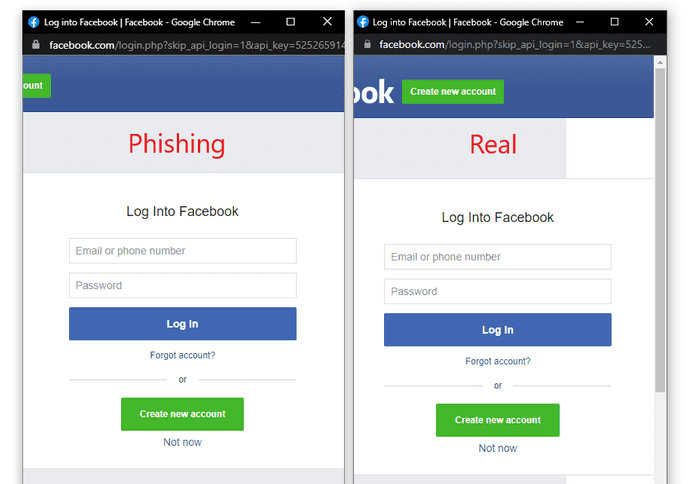

Convincing Webpage

It’s quite simple for an attacker (or anyone) to replicate a webpage. Anyone can view the source code of a webpage by right-clicking on their mouse and clicking ‘View page source’. Since the source code contains everything that makes the website look the way it does, someone simply needs to copy and paste this to a new website, make a few small adjustments, and then they have an identical looking webpage.

The source code is like the blueprint of a house that comes with the walls, doors, windows and roof all installed. Browsers read the source code and render the page to look the way it does, which is why copy and pasting the source code would give you (almost) the same result.

Almost, because sometimes things like the font or certain images don’t load properly and require the source code to be adjusted slightly.

Convincing URL?

Getting the url to look like the real url has been one of the biggest issues attackers have faced when it comes to phishing.

Many social media companies, such as Facebook or Instagram would typically own / have purchased (or even banned the purchase) of many similar domains in order to decrease these sort of attacks.

There have been multiple different avenues over the years such as using a domain name that looks similar to the original, using the actual website to link to another page (a url redirect), or more recently where attackers used a special character in the url so that when the url was read by the browser, it was read backwards.

What this meant was that a url like google.com/k9d8K3j/yl.tib would be read by the browser as bit.ly/j3K8d9k/moc.elgoog which could lead to something more malicious than google.

With this attack, however, while the actual URL is not the same as the original, with some javascript code, an attacker is able to make the URL look like it’s the same as the original website.

How do you spot the difference?

BITB attack browsers are not genuine browsers (like actual authentication pop-up windows are), they are simple HTML code that someone has built to try and look like a browser pop-up. With this, they have certain limitations that a genuine browser doesn’t have.

The usual tactic of hovering over the link to see the URL at the bottom corner will not work as a verification method.

One of these limitations is that the fake browser can’t be moved around outside of the browser window, or over the address bar. With that, here are some things you can do to test whether or not it’s a genuine authentication pop-up.

Can you move it off the webpage?

i.e. Onto a separate screen, over the URL bar at the top of your browser.

(If you’re tech savvy) Check the source code.

Are scripts being rendered from the authentication webpage (i.e. Facebook or Google)? Or from the website that you’re visiting (i.e. Canva)?

If the images are being rendered from the external website that you are authenticating your account from (such as logging into Facebook and the images are rendered from facebook.com), this is GOOD. If they are rendered from the website you’re visiting (such as Canva), this is BAD.

Originally discovered by mrd0x - bitb templates created here - information referenced from this article